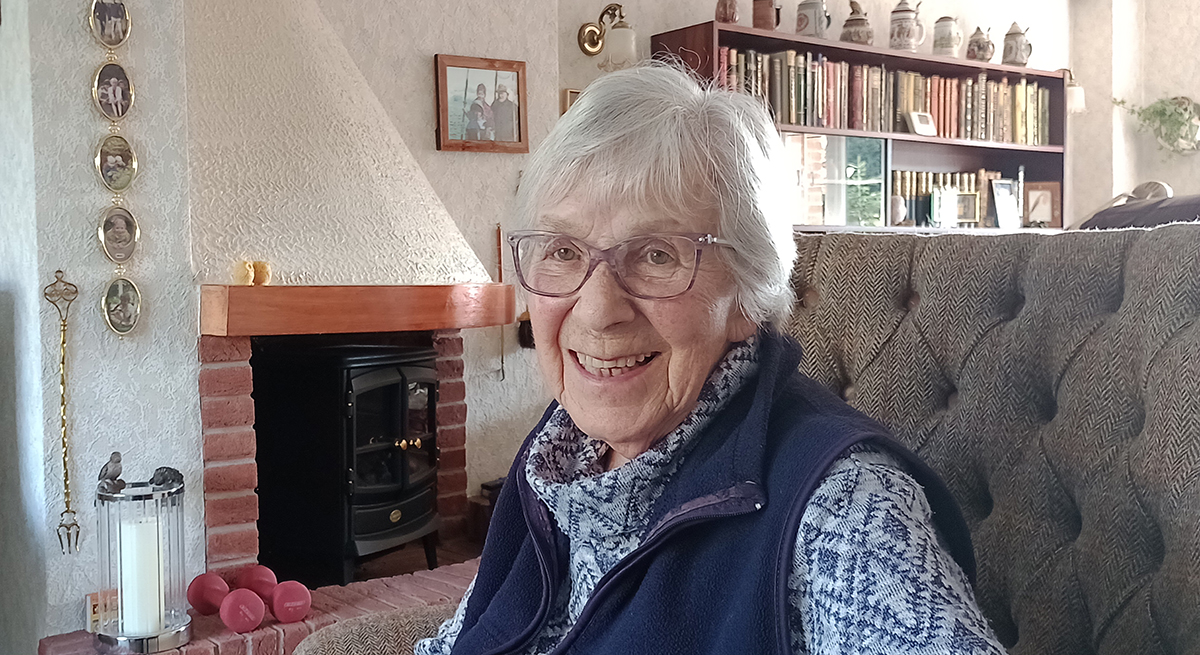

We continue Lucy Sinclair’s amazing and harrowing story which we started in the last issue. You may remember that Lucy grew up in Nazi Germany as a member of a family considered ‘unreliable’. She lost touch with her family as she moved from one city to another.

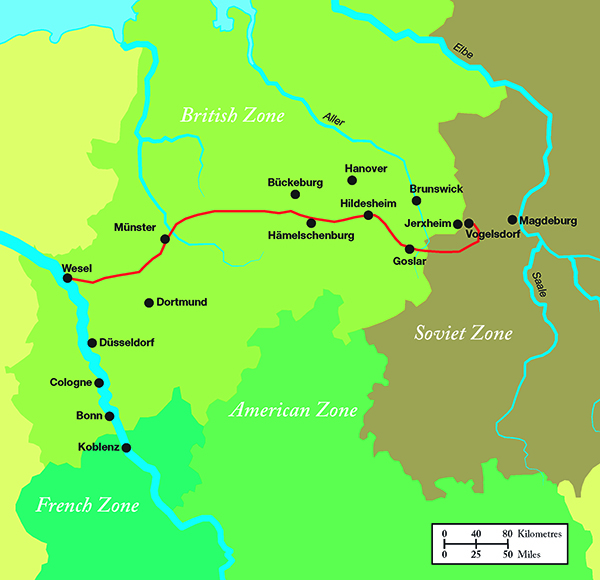

We left her, as the 2nd world war was ending, starting her trek (with her friend Erika) from their bombed-out home town of Wesel, eastwards to try and find her family.

Three hundred miles is a long way to go, through a shattered landscape with minimal transport, little money, the wrong clothes and shoes and nothing to eat beyond what they could beg. Lucy does not recall exactly how long it took them to make the journey, nor how long to locate where the Wesel families had been evacuated to. But eventually she and her friend, Erika, found them in a village to the west of Magdeburg. Their mothers must surely have wondered whether their daughters were even alive and their joy and relief when they both arrived safely can only be imagined. The war was now virtually at an end. The allied and Soviet forces met at the River Elbe at the end of April and hostilities ended in early May bringing relief to Lucy and Erika and their families and also the not unwelcome surprise that the village they were living in was to be in the American sector. For the first time in years, there was a sense that things might improve, not least since Wesel, if they could get back there, would be in the British sector.

The optimism was short-lived. A boundary-tidying exercise carried out between the American and Soviet forces saw their village transferred overnight from American to Soviet control. At a stroke of the clock, the safety of the American sector was replaced by the reverse as drunken, loot-laden Soviet troops entered the village to take over. No-one was allowed to leave other than older able-bodied men (there being no younger men left) who were taken off to no-one knew where. Suddenly life was dangerous. Women, especially younger ones, were being harassed and the families decided that Lucy and Erika needed to get out. The border with the British sector was nearby but separated by a flat no-man’s-land of three long, water-filled drainage ditches; so not easy to cross undetected.

A night-time escape attempt with others failed when a wire was tripped, triggering search lights and the party, including Lucy and Erika, was rounded up and herded into a cellar for the night. There was no ventilation or sanitation, and they had no idea what was in store for them. The next morning the pair were taken to the Soviet Commandant who established that the girls could both cook and sew and instructed them to work for him, one during the daytime and one at night. There was no choice but to agree. However, they were both in need of a wash and clothing change and obtained the Commandant’s permission to return to their mothers to tell them where they would be, and wash and change. As soon as they were back it was decided there was no option but to make a second escape attempt as soon as it was dark.

They got as far as the land between the first two ditches but then the lights came on and the shooting started. They threw themselves to the ground but Erika had been hit in the neck. For the second time in our conversation, the emotion of a recollection is visibly painful for Lucy to relate and she pauses for a moment. The shooting stopped eventually and as it began to get light, Lucy got up, took Erika with her and staggered through the final ditch and into the British sector. Army medics examined Erika but it was too late to do anything. A death certificate was issued and given to Lucy to keep for Erika’s family. Numbed by the loss, Lucy was allowed to stay for a night and was well fed with her first mug of English tea with milk. Her rucksack was examined and her metal sandwich box had a hole in the lid with a bullet inside. All that had saved her from Erika’s fate had been a sandwich box.

The next morning Lucy had to depart.

She had to go somewhere and there was nowhere but Wesel 300 miles to the west; a journey every bit as difficult as the walk in the opposite direction a few weeks before, made worse by the theft one night of her rucksack containing Erika’s death certificate. But make it back she did, to a shattered town that was beginning to show some signs of life. There was a certain amount of traffic circulating and being directed by a man as thin as a rake but nonetheless recognisable. It was her father. They hugged each other until their bones broke.

The pair lived in two rooms in one of the houses that was still standing. Like everyone else, they had virtually nothing. Lucy took on sewing and mending work in exchange for food and sometimes crockery. Not long afterwards they were joined by her mother and brothers and sister who had bribed their way out of the Soviet sector and made the long journey home. The family had endured hell, but it had survived.

As time went by, Lucy resumed her education followed by teacher-training. Then in 1950, an opportunity came her way to spend six months in England, which was experiencing labour shortages. She recalls being keen to show people in Britain that not all Germans were Nazis and found herself working at a tuberculosis sanatorium in Chelmsford. She did well and found that one thing led to another and ended up remaining in the country, finding a number of health roles that eventually resulted in meeting her first husband and the arrival of two children. Her husband’s career took them eventually to Nottingham and then when their eldest child was old enough for secondary school, they moved to Loughborough. Her husband sadly died and in time she found a new partner with whom she moved to Barrow. She finally had a place to settle but Lucy has been far from idle. She completed an education degree at Loughborough and became a lecturer at the university. Her education work also took her to Iceland on a project for the Council of Europe. Plenty to fill a book in fact, and indeed she has written one. It’s called ‘The First 80 Years of an Alien’. It’s self-published and so not available in the shops or via Amazon. However, if you would like to find out more about Lucy’s incredible experiences, the book is available at Barrow library. Alternatively, if you would like your own copy, then please contact editor@barrowvoice.co.uk and we’ll pass on your request to Lucy.

“I’ve had an interesting life,” she reflects, as I take my leave. “But not an easy one.” No, indeed.

Guy Silk