Lucy Sinclair’s story is amazing and harrowing. In a break from what we usually do, we have decided to tell the story of her travels across Europe to eventual happiness in Barrow in full but spread over two issues. In this, summer issue, we tell Lucy’s story of living in Germany during the 2nd world war. In the autumn issue we will follow her story as she survives, and leaves, Russian-backed East Germany and walks to the west.

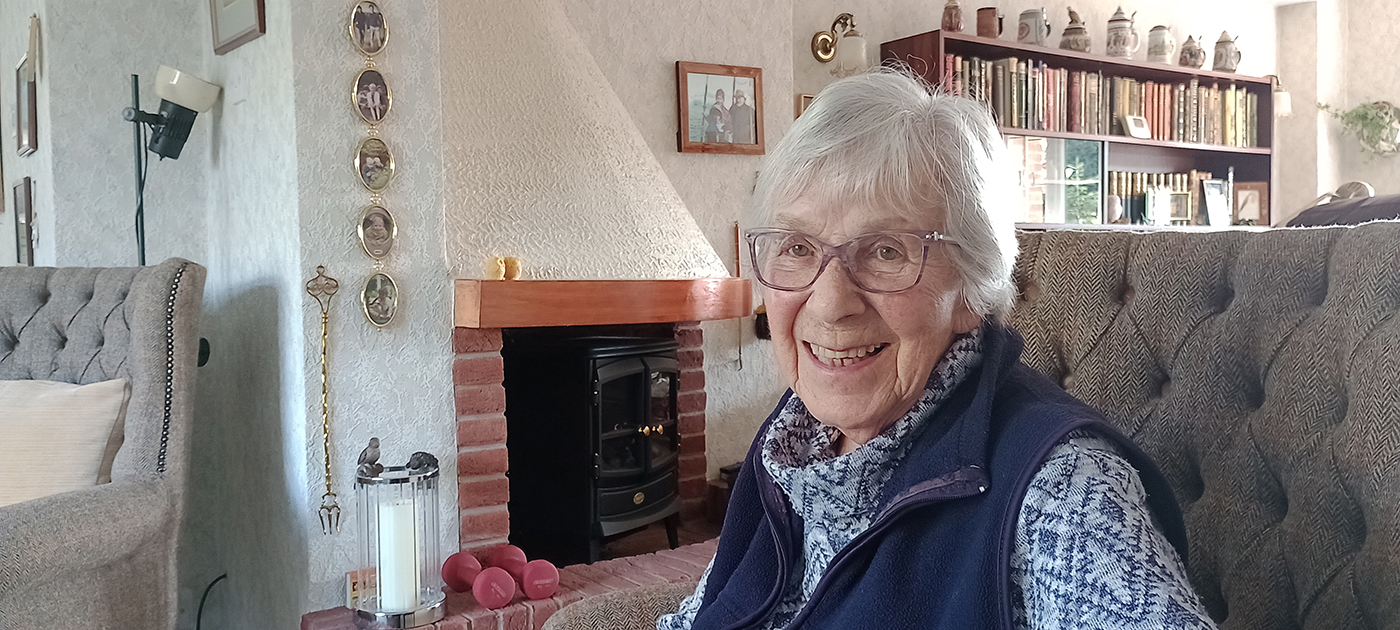

In a quiet house in a quiet part of the village, lives, quietly, Lucy Sinclair. It is a few days past her 94th birthday. We’re sitting comfortably by the window; the garden outside resplendent in the spring sunshine as Lucy begins her story. It isn’t a quiet one.

Born Lucy Moryson in 1929, the eldest of four children, Lucy’s early years were happy and uncomplicated. The family lived in Wesel on the river Rhine in the north-west of Germany, not far from the Dutch border. Her mother was German and her father was French/Polish. Neither this, nor the family’s English surname (Lucy isn’t sure where it came from) mattered. But the world around them was changing and once the National Socialists came to power in early 1933, there was enough about the family for the regime to consider them ‘unGerman’ and therefore unreliable.

In 1935 Lucy turned six and it was time to start school. The memories of her first day there remain powerfully present. There are two occasions during our conversation where Lucy begins to well up and this is the first. The children were all brought together into the main hall. All remnants of the Catholic school that it had once been had of course long been replaced by the paraphernalia of the regime including the mandatory bust of Hitler with a garland of flowers around its head. The children were all taught to make the Hitler salute and sing the national anthem, before the teachers made it clear that Adolf Hitler was their father, who looked after them, and that if they should hear anyone say anything bad about him - including their friends, their brothers and sisters and their parents - they must tell their teacher straight away. And the memory that particularly haunts Lucy, is that hands went up.

Academically, Lucy did well at school, very well in fact and possibly too well for her own good given that her family was considered politically unreliable. Although she was content to be considered insufficiently ‘German’ to be admitted to the Hitler Youth, not being a member still brought with it a sense of social exclusion, which occasionally some of her own actions made worse. When she was a little older, she found herself one of the pupils who had to tend to the garland round the bust of Hitler’s head. One dreadful morning all of the school was convened, which only happened in exceptional circumstances, normally bad ones. She recalls her name (especially her English surname) being spat out by one of the teachers and she was hauled up in front of the school for having detached one of the flowers from the garland and fixed it behind Hitler’s ear. It was a lonely and terrifying moment and she was punished by a week of enforced shunning by everyone else in the school.

Nonetheless, her academic performance remained good, and on the strength of that, the school recommended her at age 14 for teacher training, although it was possibly also a way of removing an awkward classroom presence. The opportunity was of course an order and accordingly in September 1943 she began a five-year training course at a teacher training college near Aachen, about 70 miles south of Wesel and where all of the teaching staff would be committed party members. In the event, she was there barely more than a year. By October 1944 the allied invasion had reached Germany’s western border, which was not far from the college and Aachen would indeed be the first major German town to be captured. The teaching staff hurriedly buried all of their Nazi uniforms, announced that the college was closed and told the students to go home any way they could, there being little transport available in a country that was becoming increasingly chaotic.

After a combination of infrequent bus and train journeys together with a lot of walking, Lucy arrived back in Wesel to find that the family home was empty. Her mother, younger brothers and sister had been evacuated for their own safety to somewhere near Magdeburg on the River Elbe, which was 300 miles to the east in central Germany, although exactly where no-one knew. She had no idea where her father was. She was 15 and on her own.

It can’t have been easy to know whether to stay or to go and find her mother and brothers and sister. In the event, she stayed put, volunteered with the Red Cross and found an old school friend called Erika whose circumstances were the same and whose family was likely to be in the same area of central Germany as Lucy’s. They both lived in the Moryson house by day and in the cellar by night due to the ongoing threat of bombing.

Wesel had actually escaped the serious bombing that major centres in Germany had suffered and the town was continuing to function well enough in a country that was not. But Wesel was a major crossing point on the Rhine and had become a strategic target. In February 1945 a succession of four nightly raids by the RAF reduced 97% of the town to rubble. The destruction was unimaginable and hard for Lucy to convey. She does however vividly recall an astonishing incident as one of the attacks was beginning. She was above ground and saw a woman going into labour in the street. She delivered the child (safely), tying the cord in two places with her shoelaces and cutting it with a piece of shrapnel, before escorting mother and child to the relative safety of an air raid shelter. But there was no longer any Moryson house standing. Lucy and Erika had escaped from their cellar with the greatest difficulty after the house above them collapsed. It was time to go east to find their families, joining a multitude of refugees on the move.

Three hundred miles is a long way to go, through a shattered landscape with minimal transport, little money, the wrong clothes and shoes and nothing to eat beyond what they could beg. Lucy does not recall exactly how long it took them to make the journey, nor how long to locate where the Wesel families had been evacuated to. But eventually she and Erika found them in a village to the west of Magdeburg. Their mothers must surely have wondered whether their daughters were even alive and their joy and relief when they both arrived safely can only be imagined.

Guy Silk